An Ode To Kudzu

By Sebrina Zerkus Smith | 0 Comments | Posted 09/23/2014

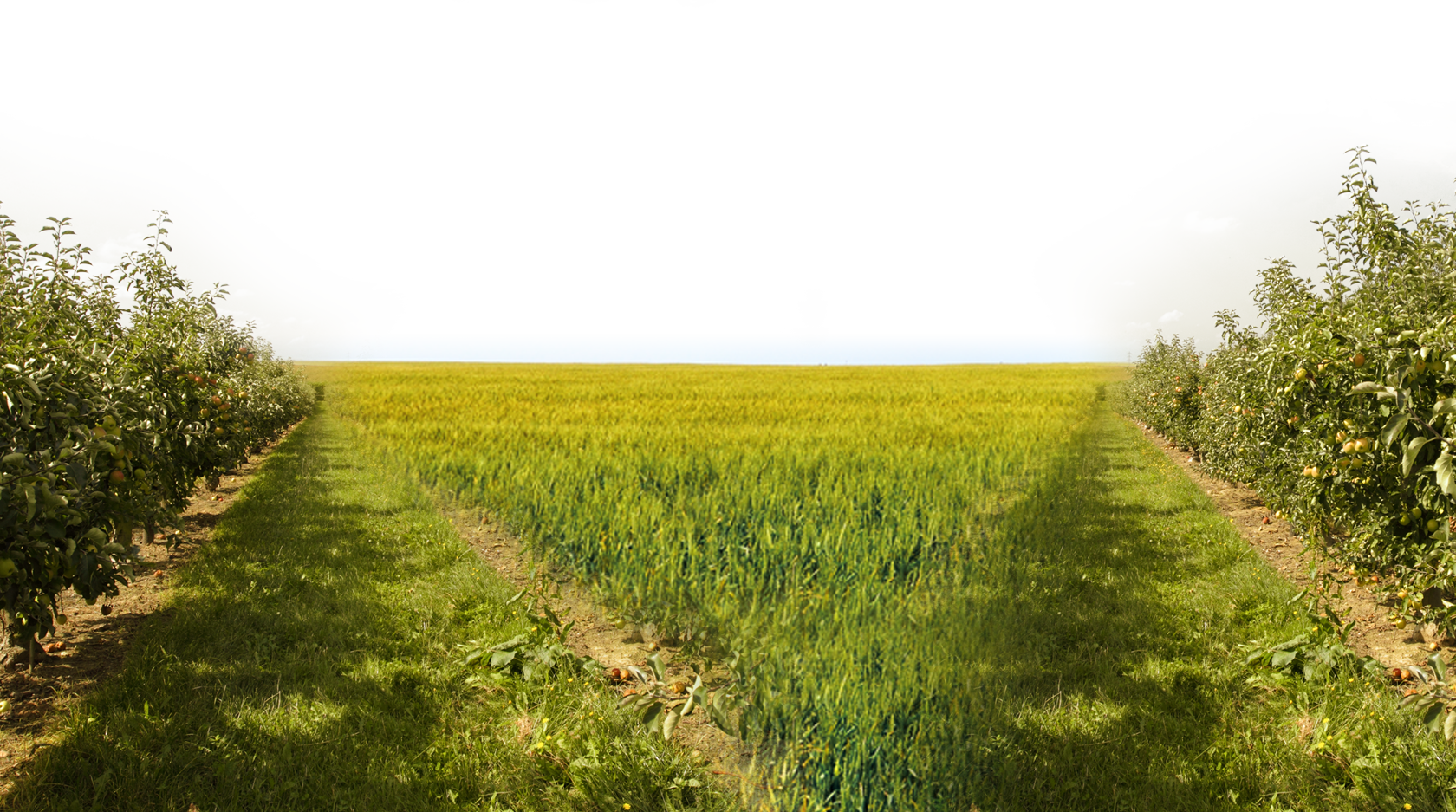

If you’ve ever spent any time in the South, you’ve seen kudzu, a vigorous climbing vine that can cover entire trees, fences and power poles. It will overtake even the most conscientious gardener in a matter of days, and is nearly impossible to get rid of once established in your yard. But I think there’s real beauty in this much maligned and decidedly iconic southern plant.

Driving through the South, especially along roads through Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi, you’ll find rolling hills resplendent with layer upon layer of kudzu — the so-called “vine that ate the South.” Its shiny leaves and sweet blossoms covering nearly every inch of available space and every type of vegetation. Monstrously relentless, yes, but also soothingly appealing, especially in the early morning, when touched by frost. In his poem, Ode To Kudzu, James Dickey wrote, “In Georgia, the legend says that you must close your windows at night to keep it out of the house.”

But there is so much more to tell about this prolific vine. For one, kudzu grows so fast and so abundantly in the Southeastern United States, you’d think it’s a native plant. Actually, it crossed many oceans before it got to where it is now.

Like my own ancestors, kudzu came to the U.S. by boat.

In 1876, several countries were invited to join the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to celebrate our nation’s 100th birthday. As a special guest, the Japanese government constructed a beautiful garden which they populated with plants native to their country. Kudzu, with its large glossy leaves and beautiful blooms, held center stage among these plants and managed to attract the attention of many. American gardeners were delighted by the plant’s amazing appearance, and began to adapt the plant for ornamental purposes.

Kudzu is in fact an ancient plant. Chinese herbalists, who know it as ge-gen, have used the root of the kudzu to treat everything from mild fever to thirst and headache for centuries. It is first mentioned in an ancient text called ShenNong, which dates to 100 A.D. In it, a drink made from pounded kudzu root was recommended for allergies, migraine headaches, and diarrhea.

But in the U.S., kudzu was prized only for its appearance. So much so, that it became the ornamental plant of choice for gardeners around the country. But in the southern states, kudzu found a home like no other. Temperate weather, fertile soil and lots of tall trees on which to climb.

In the 1920s, Florida nursery operators, Charles and Lillie Pleas discovered that animals would eat the plant, so they began selling it for forage by mail order. A decade later, during the Great Depression, the Soil Conservation Service promoted kudzu for erosion control. This led many farmers to cultivate the plant in plots in order to save the soil.

Not long after that, however, kudzu made its escape and began to take over. The plant can reportedly grow about 60 feet in a single growing season. It grew to such an abundance that in 1953, the U.S. government stopped advocating its use. Kudzu was declared a weed in 1972. But by then, kudzu had established itself as firmly as the colloquialism y’all. The rest, as they say, is history.

You might consider kudzu a nuisance, and I can see that. But I like to think of it like I think of all quirky Southern things (hats, humidity, southern witticisms, weird kinfolks, blue ceilings and sweet tea) it’s just part of who we are. And whether you admire kudzu or not, one thing’s for sure, it’ll grow on you.

Contact us

Contact us